LIBOR Transition in the Face of COVID-19 – Are We on Time?

The transition away from LIBOR to SOFR is due to become a reality by year-end 2021. With the impact of COVID-19 still evolving, some have questioned whether more uncertainty should be introduced into the market. We look at recent developments and their potential impacts.

Provided by Structured Finance Association

By Elen Callahan, Head of Research at Structured Finance Association

The decision to transition away from LIBOR[i] to SOFR[ii] or another replacement benchmark, in large part catalyzed by the LIBOR manipulation scandal that arose from the global financial crisis, is due to become a reality for the financial markets by the end of 2021. While the clock started ticking on the sunset of LIBOR in 2014 with the publication of IOSCO’s Principles for Financial Benchmarks, given the COVID-19 related turmoil currently impacting virtually every aspect of the global economy, there have been some who have suggested that maybe this isn’t the best time to introduce more uncertainty into the market. But is it realistic to think the market transition can be delayed this late in the game? In this article, we look at recent developments and their impacts on the transition.

Developments in the SOFR Benchmark

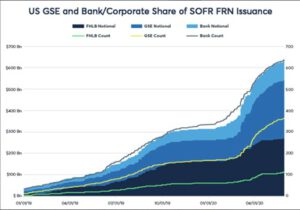

Though there was a notable slowdown in SOFR-indexed debt issuance in the winter of 2019, issuance has again picked up steam, driven in large part by FHFA-regulated entities, but also by a growing list of banks. While the average bank issuance size is small compared to average GSE issuance, the overall universe of bank participants continues to expand.

Figure 1 – SOFR Issuance by Issuer

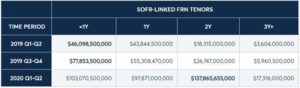

Another positive sign emerging from the data is that investors are becoming more comfortable with the liquidity of SOFR, as the volume of SOFR-linked notes continues to grow, especially in the longer tenors, with individual issuance in 4-, 6- and 7-years taking place.

Figure 2 – Tenor and Volume of SOFR-Linked Issuance

Showing significant leadership, the FHFA has been determined that its regulated entities (Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the FHL Banks) will be prepared for the transition according to the current schedule of the Alternative Reference Rate Committee (ARRC[i]). In addition to ensuring appropriate fallback[ii] language has been included in GSE contracts for the day when LIBOR is no longer available and overseeing the launch of new products tied to SOFR, the Agency has directed Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to cease purchasing LIBOR-based ARMs that mature after 2021. Furthermore, the Agency has prohibited the FHL Banks from investing in LIBOR-indexed products, and from entering into LIBOR transactions, with maturities beyond December 31, 2021.

The GSEs, for their part, have taken further steps in preparation for the transition:

- April: Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac released details about their adjustable-rate mortgage (ARM) products indexed to the 30-day Average SOFR, including eligibility, underwriting, and delivery requirements for residential SOFR-based ARMs.

- July: Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac issued a joint statement that all new credit transfer transactions would reference 30-day Average SOFR as published by the Fed, beginning in Q4 2020 for Freddie Mac and Q1 2021 for Fannie Mae. These transactions are structured in a way where, once the forward-looking 1-month Term SOFR rate is published and signed off by the applicable regulators, all previous issuance referencing 30-day Average SOFR and all new issuance will reference the new Term SOFR rate. [i]

- August: Fannie Mae released additional details about its Multifamily SOFR ARM products. Fannie stated that beginning September 1, 2020 it would begin quoting, and on October 1, 2020 accepting delivery of, Multifamily SOFR ARMs. The Agency stated that its ARM 7-6, Hybrid ARM, Structured ARM (SARM), and a new ARM 5-5 would be indexed to 30-day Average SOFR. The Agency also reminded the market that it will no longer acquire Multifamily ARM loans indexed to LIBOR by the end of 2020.

- August 3, 2020: Fannie Mae started accepting whole loan and MBS deliveries of Single-family ARM loans indexed to SOFR.

The timeline telegraphed by the GSEs and the ARRC may not work for all, and this was evident in June as entities grappled with the toll of the pandemic. In June, Pacific Coast Bankers’ Bancshares (PCBB), an entity with a focus on community banking, advocated for a delay in implementing SOFR due to the cost and additional work it was creating for smaller community banks. PCBB cited the Fed’s decision to allow loans granted under the $600 billion Main Street Lending Program to reference LIBOR, after initially stating the program would reference SOFR. The Fed’s decision not to use SOFR in this specific case was in direct response to industry feedback that to do so would divert resources from challenges related to the pandemic. Also in June, Moody’s acknowledged the slowed pace of the LIBOR transition as many entities were more focused on their immediate liquidity needs in the face of increased market volatility. The rating agency also cited the Fed’s decision to peg the Main Street Lending Program to LIBOR as further complicating the ultimate transition to SOFR. Separately, Fitch reported that small and regional banks appeared to be delaying their transition until Term SOFR was available. Fitch warned that by delaying the transition, market participants may be faced with little or no time to deal with unanticipated issues when the LIBOR benchmark sunsets.

On August 7, 2020 the ARRC released the 3-part “SOFR Starter Kit”, key information about the transition away from LIBOR to SOFR, including a recommended timeline that suggests that the ARRC continues to unwaveringly push forward with the transition. Indeed, on the same day as the ARRC release, the PCBB urged community financial institutions to continue moving forward with their transition plans.

Figure 3 – LIBOR Cessation Timeline

Compounding and Spread Adjustments

One technical point that continues to complicate the transition to SOFR is the fact that LIBOR and SOFR are different types of rates, and adjustments are necessary to make them comparable. With SOFR measuring an overnight risk-free rate while LIBOR has a credit component built in and published in a number of different tenors organizations that transitions to SOFR will have to (i) make sure they’ve accounted for the averaging of the overnight SOFR rate properly and (ii) understand the spread adjustment implications. To assist with these efforts recommendations have been provided on how to effectively use the risk-free overnight rate. Ultimately, the decision of SOFR use for market participants will largely depend on the products to which they are applying the rate[i]. For derivative products, ISDA has settled on using a compounding in arrears calculations along with a fixed basis point 5-year median spread between LIBOR and SOFR as the spread adjustment for each different tenor of LIBOR/SOFR (i.e. 1-month LIBOR to SOFR, 3-month LIBOR to SOFR, etc.)[ii]. In June, the ARCC published its final recommendation on the credit spread adjustment. It stated that it will adopt a process nearly identical to ISDA’s approach for cash products other than consumer products; consumer products will have a 1-year phase in period that would interpolate the 5-year median and actual spread differential at the time of the transition in an attempt to lessen the potential cliff effect.[iii],[iv]

Conclusion

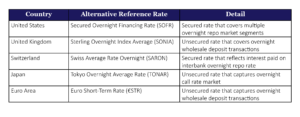

It’s important to keep in mind that the cessation of LIBOR is not just a challenge isolated to the U.S. Replacement reference rates have been identified in the five currencies in which LIBOR is published, and efforts are under way to ensure those markets are prepared in advance of the end of 2021.

Figure 4 – Alternative Reference Rate by Country

Source: Financial Conduct Authority (FCA)

And while the 2021 year-end target is still in place, there have been some instances of adjustments to interim deadlines. The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and Bank of England had originally targeted Q3 2020 as the deadline for the transition away from LIBOR in all new Sterling LIBOR linked loans. Given the challenges created by COVID-19, this deadline has been moved to Q1 2021, with smaller preparatory milestones added (e.g. lenders should be in a position to offer non-LIBOR linked products by the end of Q3 2020). The Bank of England has also delayed the imposition of increased haircuts on LIBOR-linked collateral. The increased haircuts, which were supposed to go into effect on October 1, 2020 have now been pushed back to April 1, 2021.

Can these interim milestones be pushed out without impacting the final deadline? Only time will tell but the U.K. is putting a backup plan in place in the event the markets still need to reference LIBOR post-2021 for certain tough legacy contracts and the current method of rate setting is no longer possible. Last week on October 21st the U.K. government introduced new legislation that would give additional power to the FCA to help firms transition from LIBOR to an alternative rate(s). The FCA has made it clear that they will only utilize the new power if it becomes [clear] it’s needed to protect consumers and market integrity. Additionally, the FCA stated that it cannot guarantee the methods for establishing synthetic LIBOR will be possible in all five currencies.[i]

As member banks[ii] become increasingly reluctant to continue providing daily inputs to contribute to the production of LIBOR rates, and in fact may only do so currently at the request of the FCA, it is easy to see why there is such a keen interest in keeping the foot on the gas the LIBOR transition. Having said this, however, everyone would agree that there has been much more progress with the transition of new products than for legacy contracts where many LIBOR-based products – such as securitization transactions – do not address a permanent cessation of the index rate. Without a robust, combined regulatory and legislative solution to address what to do in the absence of fallback language, uncertainty and disputes arising from these transactions will result in consumer confusion, burden the U.S. court system and ultimately challenge an already pandemic-weakened financial system. Given the tone of the guidance from the ARRC and its sister global working groups, the more prudent path is for regulators and legislators to work with consumer advocates and market participants now to address legacy issues definitively, and be ready in advance for the cutover to SOFR to minimize the inevitable burdens that such a major system transition brings.